Is China done? BoP Brief #5

This week I focus on China's struggling economy

China’s economy’s moment of truth.

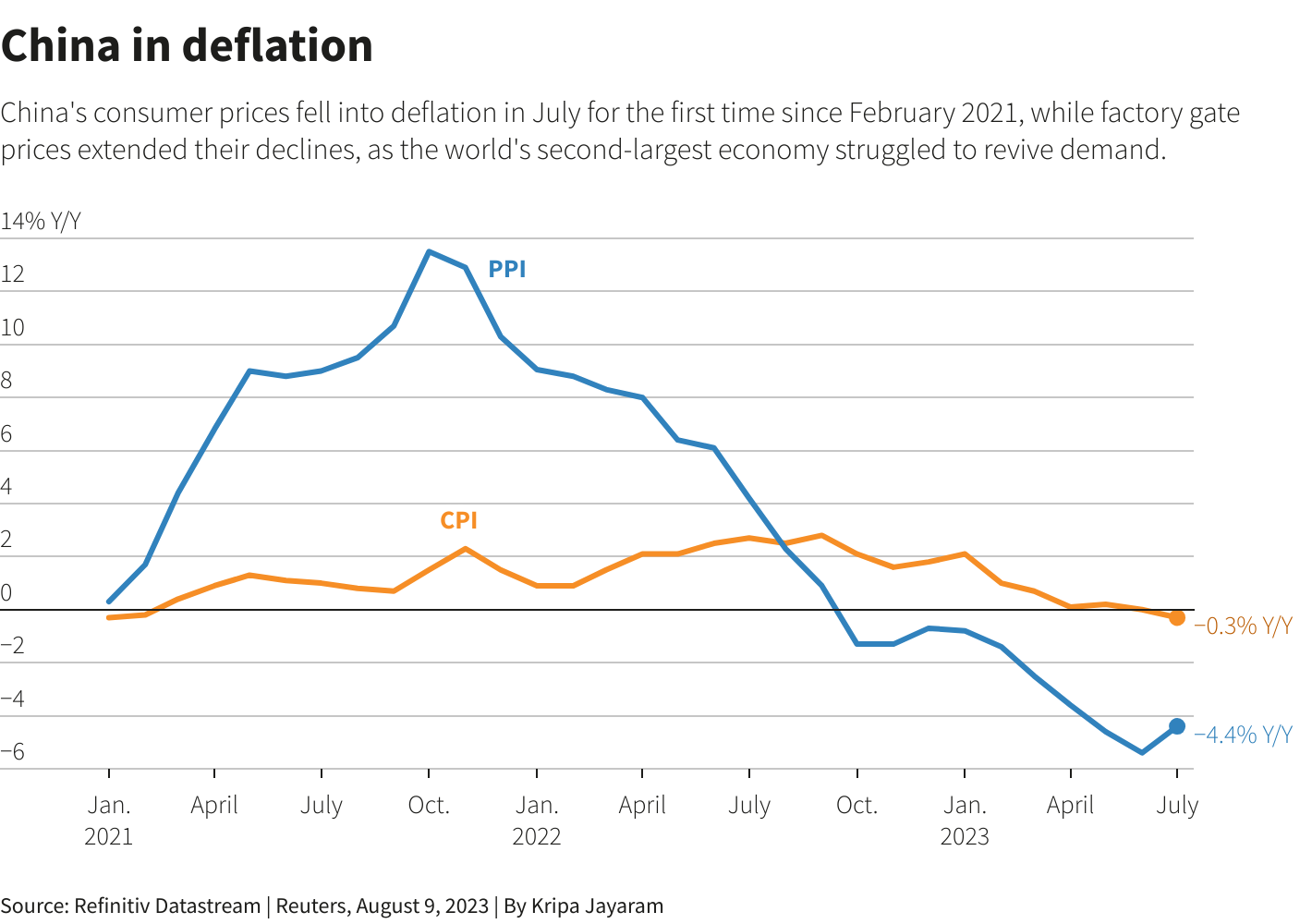

In the last few weeks, all headlines about China have been about its struggling economy. Comments from people in the country point to the real-estate crisis, rising unemployment, economic uncertainty, and deflation.

Unsettling economic data validate those concerns. Highlights of July via SCMP:

Property investments fell by 8.5% YoY from January to July, marking the lowest growth rate this year, affecting economic recovery.

Retail sales rose by 2.5% in July YoY, but this growth was lower than expected, indicating a potentially vulnerable consumer-spending-led recovery.

Industrial production grew by 3.7% in July YoY, lower than predicted, reflecting challenges in domestic recovery and foreign demand.

Overall surveyed urban jobless rate increased to 5.3% in July, and youth-unemployment figures were discontinued – last available data points to 21%

What’s going on with China’s economy?

China’s economy is suffering from a combination of previously existing problems – the real estate bubble – and the change in consumer preferences after three years of COVID-Zero.

Shifting consumer preferences towards experiences over physical goods have impacted China's export-focused economy.

A major current issue is the continuous decline in China's property market, stemming from overinvestment in real estate.

The property market's troubles have persisted for years, with a Ponzi-like dynamic involving various stakeholders triggered by a central government crackdown.

To counter the situation, China has implemented measures like stock market rule changes, currency interventions, and interest rate cuts, revealing an economy struggling due to excessive unproductive investments.

Why is this happening?

There are different narratives about what is going on in China’s economy. For more on this, I recommend Arpit Gupta's post:

Gupta summarizes some of the main narratives that explain China’s struggling economy:

Authoritarian Expropriation Risk: This perspective links China's economic difficulties to its lack of property rights protection, potential asset seizure, and President Xi's regulatory crackdown on "soft" tech.

Structural Keynesian Theory: This view attributes China's issues to imbalances between investment and consumption, driven by high savings and weak social safety nets.

Real Estate Boom-Bust: China's real estate boom leading to a potential crash, highlighting issues like low construction sector productivity and housing price bubbles.

Soft Budget Constraints: China's political system inhibits market discipline and price signals, creating "soft budget constraints" that affect economic functioning.

Should we worry?

Everything that happens in China concerns us.

It is clear that challenges in China, including declining trade, potential export of deflation, and a housing crash, pose risks that may extend beyond its borders.

A weakened Chinese economy could have a ripple effect on international markets and economies, including the US and Europe.

Beijing has taken measures to address the economic situation. However, these actions have been marginal, and a major stimulus package is yet to materialize.

Adjustment or crisis?

The key question is whether China is undergoing an adjustment or a crisis.

Dan Macklin for The Diplomat summarizes why Beijing is not pushing for a stimulus:

Beijing may see these challenges as part of necessary adjustments toward a new economic normal.

The Chinese Communist Party is moving away from a "growth-first" mindset and prioritizing "higher-quality" development, which aligns with its long-term political interests.

Capping wealth creation and stemming economic expansion may align with China's political interests.

A rapid return to high levels of growth through capitalist mechanisms could raise questions about the relevance of the nominally "communist" ruling party.

That China’s economy had to change is something that I’ve been hearing since I began to study the country almost a decade ago.

Xi has been pushing for economic change: common prosperity, dual circulation, the crackdown on tech companies, and a focus on high-end manufacturing.

It’s pretty sure that Xi won’t bail out most of the failing real estate companies because that is a sector he already wants to reduce. Diverging China’s economy from real estate, infrastructure, and cheap manufacturing, was always going to be painful.

So Beijing may see the current struggling economy as “part of the plan,” and that is likely to deter any stimulus in the short term.

On the other side, China’s commodities demand remains stable, which may indicate that China hasn’t yet fallen into an overall crisis.

Also, China’s export to the developing world surpassed the West's.

This is not necessarily “good,” but it shows a way how China could try to redirect its surplus production to compensate for its declining demand.

But that’s the “optimist” scenario.

If key strategic sectors, like the electric vehicle, began to suffer from China’s economic hardships, Xi would need to adjust his policy with the hope he doesn’t act too late.

Is China done?

A scenario is possible where Beijing fails to tame the current spiral and goes from a controlled adjustment to a chaotic crash.

Would that be the end of China as a contending global power?

Many of us have been prone to distance ourselves from the decade-long overblown prediction of China’s economy's imminent collapse.

I believe that the China of the 2020s doesn’t project the same strength and image of the “country of the future” as the China of the 2010s.

However, that doesn’t mean that China is done.

Just because of its weight, in terms of population, economy, and technological development, China can’t just disappear from the first line of the international scene. No matter how bad its economy goes.

An Era of Exhausted Powers

This is something I’ll develop more in the future. In the international context, we are not in a Thucydides Trap kind of scenario – a rising power against a decaying one – but an era of Exhausted Powers.

All great powers face internal social, demographic, economic, and cultural challenges – which could be framed into an overall context of fin de siecle of contemporary modernity.

Thus, China must deal with its long-due internal imbalances and the consequences of the policy decisions made during the pandemic – as the US and the EU have too.

How each country addresses such challenges will decide which nations will shape the course of the 21st C.

A crisis is a natural ordeal that all nations have to face eventually.

Countries we see today as very formidable powers in their moment, like the Japanese Empire or America in the 1930s, went through periods of internal strife and severe economic struggle, including famines and great desperation.

Even in the case of a severe crisis, China has the tools, resources, and capabilities to try to figure something out. The Chinese system has proven more resilient than many expected in the past, and it could become sclerotic before breaking.

And is likely that Beijing may need to adapt some of its expectations, and some adjustments might go beyond the wishes of Xi Jinping – as all government leaders have to accept.

If I’ve learned something from reading biographies and memoirs, contrary to grand historical narratives where everything fits perfectly, the present is always much more messy and contingent.

Ultimately, the decisions leaders make are the ones that define the future.

Long read: The next world war will be economic — even if the weapons don’t work

And with Exhausted Power comes the possibility of conflict and war.

Many countries are more likely to go when their economies are suffering than not when everyone has the cash to enjoy the pleasure of life.

Dylan Levi King at China Project article “The next world war will be economic — even if the weapons don’t work“, reflects on how the most critical front in the confrontation between China and the US remains the economic front, even though economic statecraft is very unlikely to change the other’s behavior.

These two sets of measures would inflict a measure of pain. Jobs would be lost or employees idled as export markets contracted and inputs began to struggle to get through. Food prices could rise dramatically as agricultural imports begin to grow scarce or much more expensive. But this assault would be devastating only in the medium-term. Chinese planners have sanctions-proofed the country’s economy to some degree, built up strategic reserves of key industrial and agricultural commodities, limited accumulation of foreign reserves, attempted with the dual circulation strategy to provide shelter from global markets, and developed alternative financial cross-border payments systems. A more complete system for macroeconomic control could be crucial to allowing China to maneuver out of any crises.

Said that an economic war plays not only with to threshold of pain of a society but also with its patience:

The people of both countries, whatever satisfaction they might take from actual or symbolic participation in or resistance to economic warfare, are likely to be dissatisfied with whatever outcomes they are told they have received.

That could very likely force governments to move to other options, whether it is a kinetic war or seriously finding a way to coexist.

This is all for today, I wish you a great week ahead.

Miquel