The new normal in the Suez Canal BoP Brief #9

The new normal in the Suez Canal, Bukele's victory and the future of El Salvador, Japan is back in the Indo-Pacific

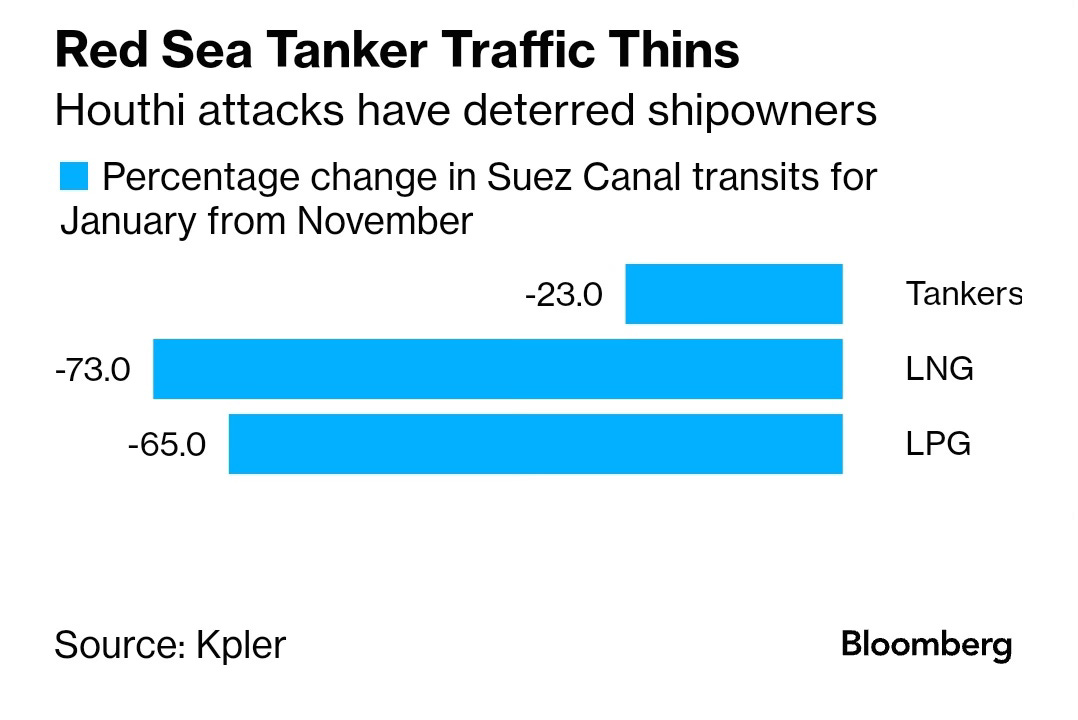

The Houthis have been attacking commercial vessels in the Red Sea for almost three months now, with no solution on the horizon.

I am fascinated by this crisis because it shows us, at the same time, the fragility of the arteries that connect the global economy as a separate segment but the resilience of a worldwide trade network as a whole.

Industries in Europe expecting components from Asia have been facing delays due to Houthi attacks, and companies like Volvo had to cease production in Europe.

While the surge in shipping prices is what gathers the most attention, the real threat to global logistics lies in delays and bottlenecks resulting from unexpected route changes and overwhelming unprepared ports and manufacturing plants.

On a positive note, as Maersk's CEO indicated, shipping firms are adapting to the Cape route for the next few months. While this keeps cargo prices high, it may alleviate supply chain disruptions, restoring regular schedules around Africa.

So, the global economy won’t collapse because of the Houthi attacks, but someone will have to pay for the price of the added disruption – though it seems we are not yet comparable to 2021.

Nevertheless, even if the Red Sea crisis is resolved, we shouldn’t expect a return of long-term stability in maritime trade routes.

A lasting consequence of the Red Sea attacks is that everyone sees that disrupting maritime shipping is a relatively low-cost, high-impact strategy. More state and non-state actors will invest in operational capabilities to replicate the Houthi attacks in the future.

After the Houthis episode, if anyone still thinks they can do business or investments without paying attention to geopolitical risks, I wish them luck!

A divided West

Not everyone is being impacted the same way by the Houthis attacks. Europe has been more affected than America. In Asia, China is already feeling container shortages – which can contribute to generating logistics bottlenecks – but emerging economies are feeling the pain, for example, Bangladesh’s garment industry.

The Houthis attack has put the West in a challenging position. On the one hand, the crisis begins as a side plot of the Israel-Palestine story, which has already European countries and the US quite divided. On the other, the US, as the country with the most powerful navy in the world, seems compelled to carry on with its self-appointed mission of protecting freedom of navigation.

At the same time, most cargo ships going through the Suez Canal do not carry a US flag, and the companies operating them – which are making some money out of this – are European.

As a result, we have witnessed a divided response to the Houthi attacks.

The US and the UK launched Operation Prosperity Guardian, directly targeting Houthi positions – also with the support of Greece, Denmark, and the Netherlands – while countries like France have preferred just to escort the ships under EU flags and not directly engage with the Houthis – taking down missiles and drones once the attack began.

Despite its efforts, the joint mission between America and Britain hasn’t been effective in deterring the Houthi’s menace. And some would say it only helps to make things worse. For now, the US and UK-flagged ships have been rewarded with an extra risk premium cost on their insurance if they try to cross the Suez Canal.

Strategic bombings are not going to take the Houthis down – the Saudis tried that for years with not much success – and we know there are not going to be boots on the ground in Yemen. Also, being made enemy number one of “The American Empire“ has given the Houthis more street rep among the so-called “Resistance Axis.”

The EU has taken its time – maybe waiting to see if the situation cooled down by itself – but it is finally assembling a mission that will be under Italian leadership and will count on the strong participation of Mediterranean navies like Greece.

I am curious about what Spain is going to do. Due to Pedro Sanchez’s administration's pro-Palestinean position, Spain refused to participate in Operation Prosperity Guardian but also vetoed the use of resources from the EU’s Atalanta Mission – in charge of countering Somali pirates – against the Houthis.

However, regardless of where they stand on the Israel-Palestina issue, all Mediterranean nations are being harmed in one way or another by the Houthi attacks.

I wrote an article about this for World Politics Review:

Support for de-risking from China and the extra cost it may incur on European consumers is usually based on the idea that the jobs and industries currently in China will be brought back to Europe. If, however, instead of re-shoring to domestic manufacturers, European companies simply near-shore to Morocco or Turkey, that could provoke the wrath of European voters. Add to that the tensions over migration from these countries to Europe, and near-shoring could easily become a source of strain in North-South Mediterranean relations. With a series of important elections in 2024, this is a political risk to watch, particularly against the backdrop of the current surge of right-wing populist parties across Europe.

Amid the increased uncertainty surrounding extended maritime routes, Mediterranean nations can capitalize on the preference for shorter supply chains and the de-coupling of Western economies from China. Nevertheless, in a tightly interconnected system of logistics networks, significant disruptions in the Suez Canal are likely to undercut the significant advantages these new patterns of connectivity bring to the Mediterranean, especially given the possibility of escalation between the U.S. and the Houthis.

Please let me know if you don’t have access to the article.

There are many other angles in the Red Sea crisis, so will go back to this in the future.

Bukele made El Salvador Safe. Can he make it rich?

President Nayib Bukele achieved a sound victory with 87% of the votes for him. These numbers might be hard to believe, but it is easy to see why a majority of Salvadorans would be supporting him.

The international press has pointed out the possible human rights abuses of his government. Still, when gangs rule and a country lacks a minimum level of security to be a functional society, few liberties can be enjoyed.

Bukele’s methods can be harsh, but the numbers seem to back him, with murder rates down 70%. El Salvador has indeed passed from being the country with the highest murder rate in the world to the one with the largest incarceration rate.

Still, I can see that as a change that most Salvadorans can welcome – even if we ignore that El Salvador is now also the country with the lowest murder rate in the Western Hemisphere.

Securing the monopoly of violence is the sovereign's first source of legitimacy, but can it be the only one?

Juan David Rojas and Geoff Shullengberger approach this question in their analysis of Bukele’s revolution. I share their conclusion that once El Salvador has achieved a decent degree of stability, Bukele will have to back his position with a sound economic policy.

One can have different positions about Bukele’s bit for Bitcoin, but at least it shows a government willing to take risks and innovate. In this sense, Bukele has been opening El Salvador's economy, attracting foreign investment, and boosting the service sector to cater to the expat digital economy.

If Bukele manages to consolidate El Salvador's position in the digital services economy and preferably goes beyond that, securing long-lasting growth for the country remains to be seen. But now Bukele has the power – and most likely the popular support – to implement whatever economic policy he sees fit.

Bukele wanted to have El Salvador’s future on his hands, and now he has it. His leadership in the economic policy will decide if he is really up to the task of becoming Latin America’s Lee Kuan Yew.

It is important to pay attention to Bukele’s future because he is relevant not only for El Salvador but for the whole region – and even beyond – because his success will prompt other leaders to try to follow his example.

Japan is back in the Indo-Pacific.

Kishida is not enjoying much popularity at home, but Japan is gaining love abroad.

Like everyone else, Japan is preparing for a potential war with China. The country is reinforcing its alliances in the Indo-Pacific and its industrial capacities at home.

Still far from the pre-WWII era, but Japan seems to be taking the horizon of war much more seriously than most Western European countries – for obvious reasons.

Japan and the Philipines are close to signing a troops pact.

How Bejing blew up its relationship with the Philipines always fascinated me. As you know, I have a thing for populist politicians, so I followed Duterte’s campaign and presidency quite closely. When he was in office, Duterte was more than willing to reboot relations with China and become closer to Beijing.

Xi Jinping, who, as we know, has a neighborhood fond of him, paid Duterte’s opening, doubling down on China’s reclamations in the South China Sea. Now Duterte is gone, and the Philipines are not only back on track on their relationship with the US but also getting close to Japan. All hail the Chairman.

Japan is an indispensable ally for the US security nexus in the Indo-Pacific.

It is well known how Japan became the logistics powerhouse of the US armies in their operations in Korea and Vietnam – and how that helped to fuel the postwar “Japanese economic miracle.”

However, Japan’s role is still vital for the US efforts in the Indo-Pacific. Japan is going to expand its shipyard capabilities to repair US Navy ships. Why is this not happening in the US? Well, there is a cost-effective logistical reason: it makes more sense to repair ships near where they will be deployed. However, a much more troubling reason from the US side is America’s loss of industrial culture and muscle.

And I find here a connection with the case of Nippon Steel's purchase of US Steel. If a country believes that a possibility of war is on the horizon, securing and reinforcing its steel production is a must. Nippon Steel’s CEO used precisely the argument that it is necessary to pull resources to counter China’s steel production to ease the worries of American critics.

As I argued for Unherd, he does have a point, but that is not an excuse for not asking why it is not an American company that is buying Nippon Steel and becoming a global steel powerhouse instead of a Japanese company.

Said that, if this is the turn things are going to take, and Japan is going to be the country repairing US ships and building the stuff that America’s economy can’t, it makes all the sense in the world that Nippon Steel's global production has the means to compete against China.

It is also vital to notice that Japan is reinforcing its military capabilities, signing a deal to buy 400 tomahawk missiles from the US.

Other things I’ve recently published:

Can Javier Milei be a partner of the US in Latin America against China?

My latest Op-Ed for the Orion Policy Institute explores if Milei, despite the many uncertainties, could be an ally of the US to counter China’s influence in the Americas.

For most Taiwanese China is not the Biggest Concern

My read on Taiwanese election result.

China is not ready to invade Taiwan (yet)

My quick take on the last reshuffle/purge in China’s Rocket division – I wrote it before reading about the rumors of rockets filled with water instead of fuel.

Sorry for the silence in the past few weeks. A combination of personal matters and a project I had to hand in at the end of January kept me away from the newsletter. But I am happy to share with you that I have already submitted it – I will let you know more about it in the next few weeks. That said, I expect to be here more often from now onwards.

Have a great week!

Best,

Miquel