Understanding Populism (I)

To understand 21st C. politics we need to understand Populism

Populism is the central political event of the early 21st C.

To understand the epochal political upheaval we are witnessing worldwide, we need to understand Populism.

As it happens, 2023 ended with the victories of Javier Milei in Argentina and Geert Wilders in The Netherlands. This year has already seen the electoral success of Nayib Bukele in El Salvador and Prabowo Subianto in Indonesia.

With nearly sixty elections expected to take place in 2024 around the world, we will keep hearing a lot about Populism.

Once a Populist Titan emerges to rally the politically orphan masses of "deplorables" (sic) against the crooked elites, the nation's political board will revolve around them.

The media, always hungry for attention, won't talk about anything else. Promptly, the foe and friend division will be drawn along the lines of support and opposition to the Populist Insurgency. Establishment parties will realign their political programs and discourses to compete against the populist challenger.

Nevertheless, despite the centrality of Populism today, it is still a largely misunderstood phenomenon. The label populism remains confusing and is more often used as a pejorative term than an analytical one.

How couldn't it be confusing to use a label that can be used for candidates so different from each other, such as Hugo Chavez, Javier Milei, or Donald Trump? But what makes it confusing is when the same label is often used to (dis)qualify leaders with little to do with Populism, like Vladimir Putin, Viktor Orban, Xi Jinping or even Emmanuel Macron.

The pejorative use of Populism doesn't really help to understand the power of the phenomenon. For many, a Populist is just a post-liberal strongman that "we don't like." But confusion about Populism does not only come from its detractors but also from their sympathizers.

A new breed of dissident conservatives and nationalist analysts now use it as a positive category to fit anyone who seems to talk for the main street conservatives against the "globalist elites" and sometimes negate the category of Populist to those movements with whom they don't share a political program.

However, we need to be cautious because ideologically rigid definitions don't allow us to understand the diversity of social movements covered by the umbrella of Populism and how they can differ from other political forms.

Given the centrality of populist movements around the world, it is crucial to have a clear understanding of their nature and centrality in contemporary politics. That's the only way to grasp the potential political risks and opportunities that emerge from Populist insurgencies.

In this first installment of my analysis of Populism, I'll focus on defining the components of Populism and understanding its use as a political strategy. In a future second part, I'll focus on presenting how a populist performs once in power, checking both their transformative potential and their limits.

What is Populism?

The first point we need to understand is that Populism is not an ideology or a program; Populism is a form of making politics.

That means that Populism is not confined to a particular right or left ideology but is a discursive strategy that various political movements across the ideological spectrum can adopt.

Although I am presenting my own views here, I am going to work with Ernesto Laclau's definition of Populism, which more or less goes as follows:

Populism is a form of political discourse that articulates the demands and interests of a "people" against an established "elite."

Ernesto Laclau was a post-structuralist academic born in Argentina who developed most of his career in the UK. He was a hardcore Peronist and a political advisor for the Kichners. I am curious about what he would say about Milei. He would definitely hate him on ideological grounds, but Milei's victory has indeed validated most of Laclau's theories about Populism.

I have my differences with Laclau's sociological and political views, but he is by far the author who has influenced my understanding of Populism the most.

The people in mass politics

To understand the appeal of Populism, we need first to understand the power of the word "The People" in modern societies.

A key element that distinguishes the Old Regime from the New Regime is that almost all modern political systems are legitimated by the appeal to the people's rule. That is as true for the "We the People" that opens the American Constitution as "all power in the People's Republic of China belongs to the people" of the Chinese Constitution.

We can say that almost all modern political regimes have a populist founding myth where the People rose up against an Evil Other – a colonial power, a dictator, the king, a social class, etc. – and took the reign of their destiny and legitimated the new form of government.

The founding populist moment passes when there is a process of institutionalization. That means that the symbolic sovereign power of the People is transferred to the State and will be mediated by a political, bureaucratic elite according to a certain set of regulated practices.

The fiction of the unity of the people is then fragmented into different interest groups, and politics is channeled through ordered administrative procedures. Depending on the nature of the political movement that gives birth to a new regime, that process of institutionalization lasts longer, and sometimes it never fully occurs.

This process does not necessarily need to be "real," but most founding myths of modern political regimes rely on this kind of narrative. The legitimacy of "popular" governments lies in their ability to express the will of the people. That naturally creates an inherent tension around the question of how true it is that the people are in power and the existing power serves the interests of the people. Such tension between the people's will representation and institutionalized power is what can allow for the formation of populist uprisings.

Populism vs Institutionalism

In an institutionalized regime, when a group of citizens have a problem, they usually present their demands to the existing administrative channels. If there is a strong institutional regime, the government will be able to absorb the demands of the concerned citizens without affecting the system or cracking down on dissent if they are seen as a danger to the established regime.

When the system cannot absorb a growing number of demands, and there is a widespread feeling that the ones in charge do not act on behalf of the many, but for the benefit of the few, there is a window of opportunity for a populist insurgency to form.

Populist movements will argue that the founding pact has been broken and a corrupted elite has captured the institutions that were supposed to represent the people.

Opponents of Populism usually present an Institutionalist narrative, defending that the existing institutions are already the real representatives of the people's will. In democratic regimes, we will see an appeal to the transparency of the existing institutional procedure, the rule of law, and the need to trust experts to channel the "will" of the masses.

In more extreme anti-populist reactions, for example, during the Brexit referendum, the masses will be directly deemed as irrational and untrustworthy and thus shouldn't be trusted with a direct say in live-changing matters.

To a certain extent, all modern politics have a component of tension between populist elements and institutionalist or elitist rhetorics. We can find traces of Populism in all modern mass political discourse, but of course, not always with the same centrality or force.

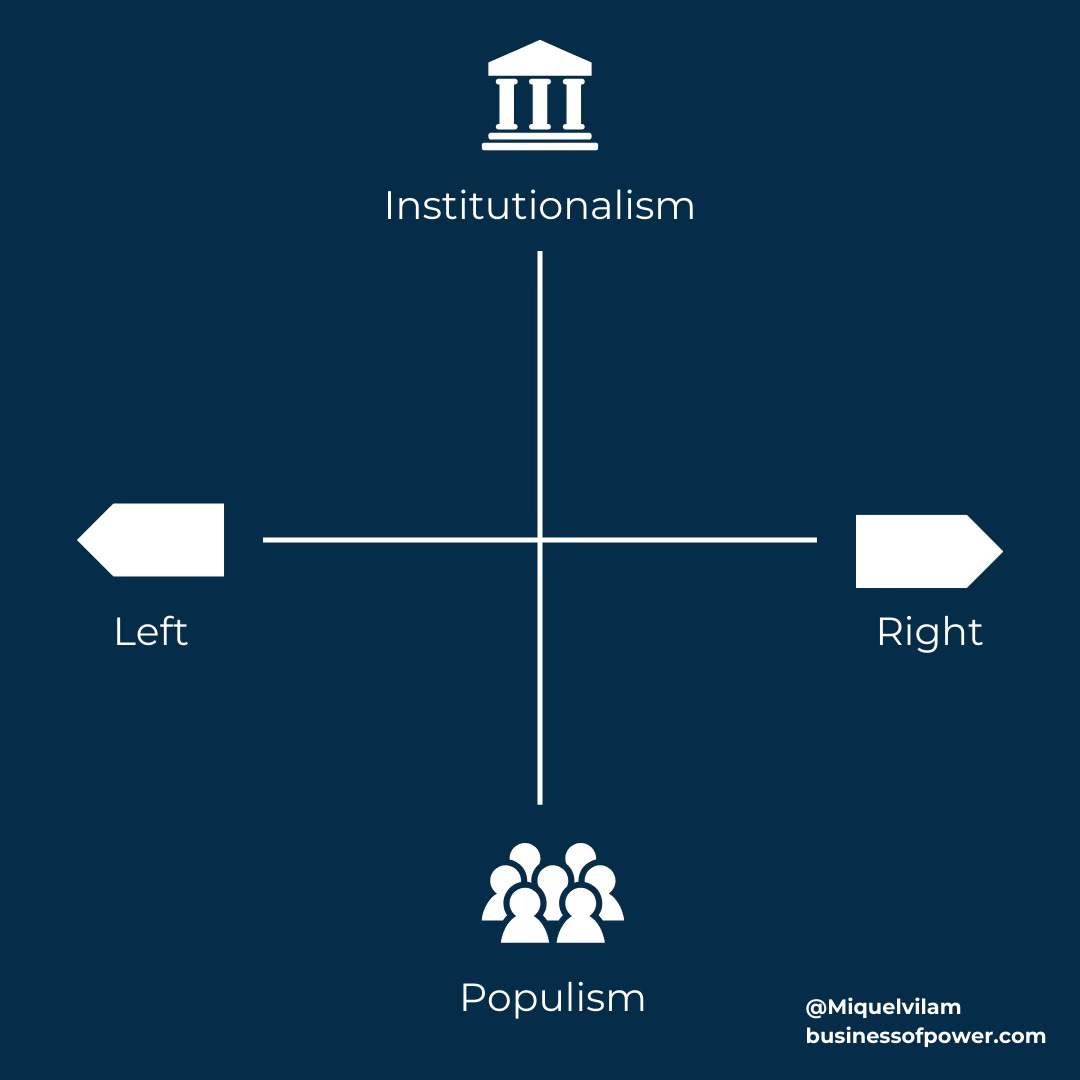

In this sense, Populism might be better understood in terms of a gradation, and we could add a new political axis apart from the classical Left and right division, opposing Populism vs institutionalism.

The Populist articulation

However, here I am more interested in those social eruptions that are more clearly populist, instead of the ones that just introduce some populist gestures in their discourse without really embracing a full-on populist form.

Let's focus on how a populist insurgency emerges. The expression that better condenses the feeling of the populism moment is "Enough!." The people are just fed up, and they want to get rid of everyone who has anything to do with the current State of things.

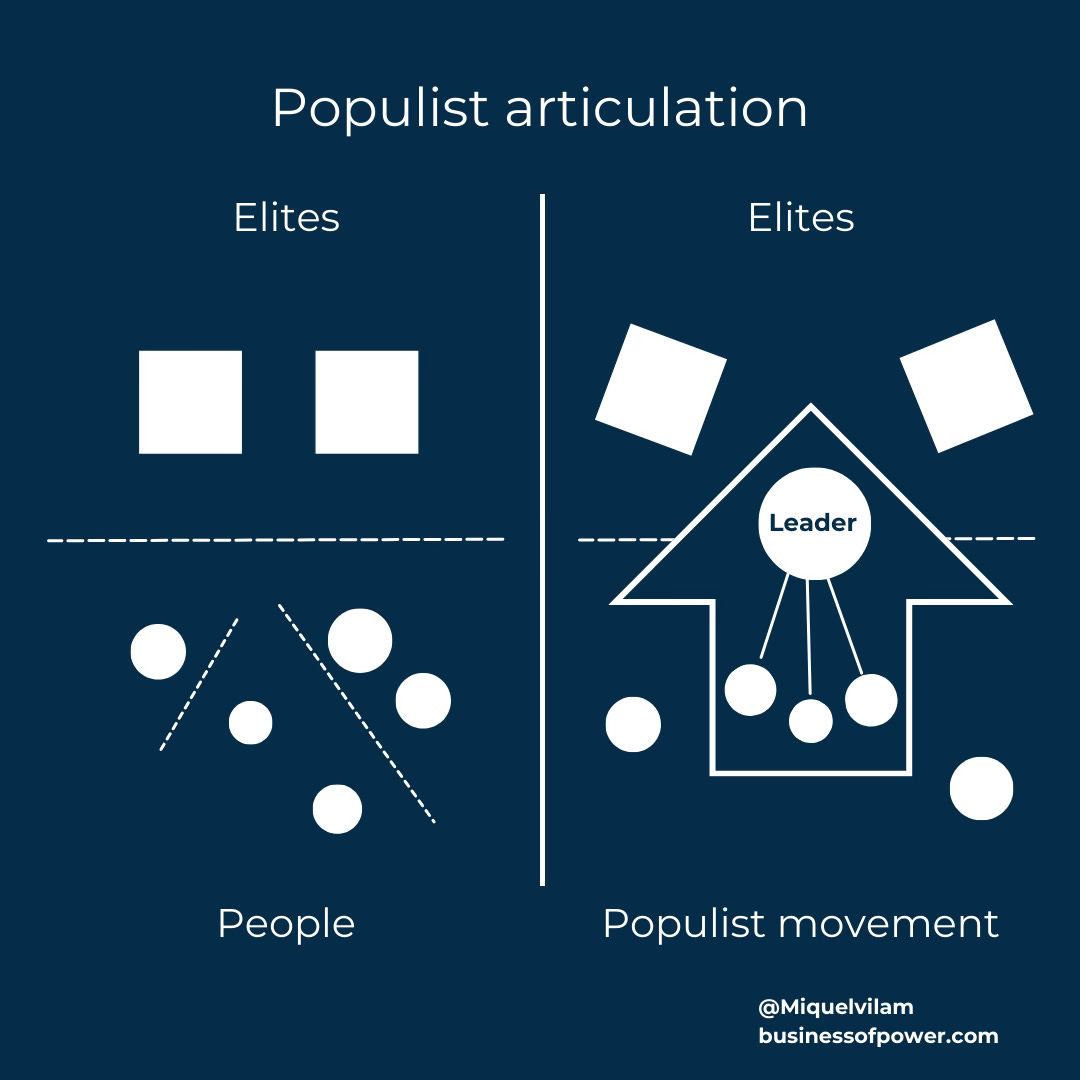

But the "People" will still need to be given form so the shared feeling of grievances can find mutual understanding and be translated into political action.

What makes Populism different from classical political coalitions is that a populist articulation aims to dissolve the different groups into a unified idea of the People. Where populist movements are really good is reaching out to individuals not already organized in some kind of political group or union, breaking traditional allegiances to form new ones.

That doesn't mean that a populist coalition in the real world won't have to deal with political representations and quotas of different groups that will be part of the movement – and usually will be the ones offering technical knowledge and grassroots organization muscle. However, there is a tendency to work around a system of institutionalized factions.

So, we can say that a successful populist narrative will be organized around three elements.

People vs Elite

The populist movement organizes the political arena around the lines of People vs Elite instead of traditional Left vs Right. All existing political parties are presented as different sides of the same coin. This is an important step because traditional Left and right divisions must be broken so the political conflict is not kept organized around the lines comfortable to the establishment.

Even if, like in the case of President Donald Trump, he runs for the Republican party, he has a rhetoric opposed to the traditional establishment of the Republican party, lumping them together with the Democratic party elites. That is also what helped him in 2016 to attract part of the Democratic electorate, or at least convince them not to vote for Hillary.

An important caveat is that substituting the centrality of the Left vs. Right axis for the People vs Elite axis doesn't mean that the populist movement doesn't have an economic or social program that could be considered Left or Right. For example, Javier Milei was very vocal about his Libertarianism and opposition not only to the Elites – Caste – but to the Left specifically.

Nevertheless, changing the way the boundaries of the friend/foe distinction is done allows to reach out to disenchanted citizens with the political system that, if they were following their traditional Left/Right allegiances, wouldn't vote for the populist candidate.

A classical discursive appeal would be: "Even if you have been a Left/Right voter all your life, now is the moment to leave those differences aside because the real conflict is not Left or Right but between the People against the Elites. And we are the People."

Institutional challenge

Here comes a proposal for change. The existing regime needs to go.

The critique against the establishment takes the form of a critique against the current institutional setting and a desire to shake down the system. There are different gradations of how deep that proposition of change could go, but there is always a clear goal of deep reform or even the founding of a new regime.

Sometimes, that is crystalized in a call for new constitutions, elimination of certain institutions, exiting international organizations, or reform of the electoral system.

The institutional challenge usually goes beyond the formal bureaucratic powers of the State. That also can encompass breaking with perceived pernicious economic monopolies, academic and media cartels, the configuration of the party system, etc.

Charismatic leader

Because a Populist movement wants to articulate a multiplicity of disperse citizens, sentiments and groups, it needs a great leader that helps to give coherence to the movement. Taken to an extreme, sometimes supporters of a populist movement may only agree in that they agree with their leader.

For example, Juan Domingo Perón would be the greatest example of a populist leader able to build an extremely extended coalition. From communist guerrillas like the Montoneros to anti-communist armed groups like the Triple-A – eventually, things got out of hand, and both factions ended up killing each other.

Ussually, the pure breed populist leader is a political outsider, maybe someone famous or successful in a career outside politics, or a politician that has always been known for expressing his own ideas without caring about the official party line.

Doesn't really matters if the leader in question comes from a plebeian social class, but he needs to be able to relate and naturally move in a popular cultural setting. It is important that he is someone who can create a direct and special relationship with his supporters without the intermediation of institutions, organizations, unions, etc.

To summarize, a successful populist strategy is the use of the force of the Many, led by the One against the Few:

Why Populism works? (to win elections)

Populist movements have always existed, and as said earlier, some kind of populist element can be found in all modern mass political discourse.

However, some dynamics of contemporary societies make Populism especially successful today.

Fragmented Societies

In my opinion, social fragmentation and the rise of a low-trust society is what explains why Populism is today the most effective political strategy to challenge an existing regime.

Back in the day, social institutions had more strength than they do today; most citizens in modern societies would be attached one way or another to churches, workers' unions, political parties, clubs, companies, etc.

Families and organic communities were stronger. Today, we live in a low-trust society with high feelings of social anomia, a loneliness that makes traditional ways of organizing politics more difficult.

However, the feature of 21st-century societies is their internal fragmentation, which is more profound and difficult to manage than in earlier decades.

Populism is a good strategy for fragmented societies because, thanks to its nimble and malleable identity, it makes it easier to give form and unite a diverse set of discontent groups. That is also why the nationalist element is very important for populist movements, because it provides the shared identity that allows homogeneity among supporters beyond ideology or class.

Institutional Obsolescence

We cannot separate the current social fragmentation in developed societies from the decay of its existing institutions. Especially the loss of capacity of the nation-state to impose a shared identity among all its citizens.

Higher immigration is part of this problem, but growing digital forms of socialization are also to blame because online socialization spaces tend to produce niche cultures. And the current institutions are just not ready to deal with this. Inclusivity policies have often eroded any strong common identity that institutions could use to integrate diverse groups of citizens.

To that, we should add another different set of crises and technological developments that states are having problems keeping up with, and problems like corruption and state cooption that fuel the feeling that current institutions just don't work.

Because this institutional crisis is felt all around the Western world and beyond, Populism finds a suitable environment to grow.

Entertainment Politics

Populism is much more interesting and entertaining than conventional politics. I don't say this as a critique; I say it as a fact.

Electoral politics, nowadays, have become mostly a show business – another day, we can talk about the problems of that. But that is not the fault of populist candidates. Spectacle politics was already there, Populists just do it better.

Populist candidates usually speak their minds in ways that grey career politicians don't often do that connect much better with the public. Also, even if the candidate is not very good at this, populist movements are much more naturally connected to popular culture, producing memes and jokes difficult to meet by agencies working with establishment candidates.

In this sense, Populism is to institutional politics what guerrilla warfare is to conventional war. And as happens with guerrillas, they won't always win, but they will change how war is fought.

Here, I must say that the entertainment populist candidates produce is not only for their supporters but also for their detractors. Just think about how central Donald Trump is to the liberal media. Some journalists have made their entire careers around his figure, and they don't even want you to vote for him!

And that happens every time a populist candidate begins to gain traction. A populist candidate doesn't need to win an election to revolutionize his country's political landscape. If he or she is good, they will just dominate the conversation without the need to sit at the table.

The centrality of Populism

Because Populism is not an ideology, it is a form of doing politics, anti-establishment political movements with very different agendas can take populist forms. Some common elements include nationalism, protectionism, and the use of executive state power.

But as Javier Milei shows, not all populist candidates need to support a social protectionist economic policy, especially when that's the policy that represents the existing political establishment, as was the case in Argentina.

So, as I might explore in a future piece about the "geopolitics of Populism," expressing sympathy or trying to tie together political movements just because they are Populist might not always make much sense.

Populism, if done well, can be an effective political mobilization strategy. But not every candidate incorporating some elements of populist strategies is a pure breed populist. In Europe, for example, not all right-wing nationalist parties are populist movements, even if they adopt some populist forms and share talking points.

The fact that Populism is a form of doing politics and not as much an ideology doesn't make irrelevant the question of "who is a real pure breed populist candidate". I think authenticity is important for a populist leader to succeed, and you can feel the ones who are playing the Populist instead of being genuinely Populist.

I have a method, what I call the Punk Bar Test, that helps me distinguish pure-breed populist candidates.

Try to picture that leader in an old-school punk, rock bar, or pub. You know, the kind of places I have in mind. Poorly illuminated places that play good music, where passing the mop might do more harm than good, and where a hole in the ground would be much more hygienic than whatever they have in the bathrooms.

If you can picture the prospective Populist candidate in that setting looking comfortable, with a beer in his hand, having a good time chatting with the regulars there, then no matter their upbringing, background, studies, or how much money they have, you will have found here a genuine Hero of the People.

If you don't believe me, try the test by yourselves and let me know your opinion in the comments.

This is all for this week, I hope you like it. As always likes, comments and shares will be appreciated.

Have a great weekend!

Very well written article! I certainly agree with your definition of "populism" here, and think that more people should read this article so as to better understand what "populism" is really about...

In terms of the "bar test", there are a lot of people in politics who I could think of who would pass this test, though there are even more who I think wouldn't be able to pass the test.. let's just say that there's a reason for the popularity of Donald Trump, Boris Johnson or Doug Ford among working-class voters which eludes the "elites", and a major reason is that they pass the "bar test", while Hillary Clinton, Steven Del Duca and Rishi Sunak probably do not...